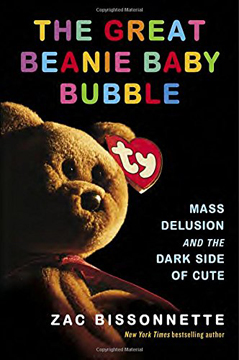

by Zac Bissonnette, author, The Great Beanie Baby Bubble: Mass Delusion and the Dark Side of Cute

Between 1996 and 1999, Ty Warner earned more than a billion dollars with a single line of understuffed beanbag animals that retailed for $5 each. In my new book, The Great Beanie Baby Bubble: Mass Delusion and the Dark Side of Cute, I chronicle the story of how those animals became the strangest speculative bubble in the history of capitalism.

Between 1996 and 1999, Ty Warner earned more than a billion dollars with a single line of understuffed beanbag animals that retailed for $5 each. In my new book, The Great Beanie Baby Bubble: Mass Delusion and the Dark Side of Cute, I chronicle the story of how those animals became the strangest speculative bubble in the history of capitalism.

Today, Warner boasts a net worth of more than $1.7 billion, mostly invested in properties such as the Four Seasons Hotel in New York City (with an approximate value of $900 million); the San Ysidro Ranch in Montecito, Calif. (where John Kennedy honeymooned and Jessica Simpson got married); and a $150 million mansion in the same town.

But before all that (not to mention some tax problems), Warner had 12 employees in a suburban Chicago office, and his company labored to sell his line of Beanie Babies to retailers who complained that they looked cheap.

Here are a few of the traits and tactics that eventually made Ty Warner a billionaire.

1. Obsess over Every Detail

In the early days of his business, when he was running it out of his condo, Ty Warner personally trimmed and groomed every single plush cat he sold before it was shipped to a retailer. An early high point in Warner’s plush-focused compulsiveness came at the photo shoot for the cover of Ty Inc.‘s 1988 catalog—the first the company ever distributed to retailers. A simple foldout brochure printed on glossy paper in full color, the cover featured Angel, a white stuffed cat with a Ty tag around the collar and a pink ribbon, on a black background with no props of any kind. The photo shoot was a last-minute affair in the office of a local printer.

“Ty would look at it and say, ‘Nah, it’s not right. Take another picture. It’s not right. I don’t like it,'” remembers Patricia Roche, Warner’s girlfriend and only employee in the early days of the business. The single-image photo shoot took nine hours, but the result is a cover that is equal parts regal and seductive—to the extent that a stuffed cat can be either of those things.

2. Ask Everyone for Advice—Everyone

Warner, whose education consisted of one year studying drama at Kalamazoo College, never used expensive marketing consultants or focus groups. Instead, as someone trying to sell a consumer product to the masses, he simply sought the feedback of everyone around him. The reporter who interviewed him for People magazine in 1996 remembered that she couldn’t figure out who was interviewing whom, because Warner spent so much of their conversation asking for her opinion on new designs.

One executive remembered Warner wandering the office, carrying artists’ renderings of new animals he was contemplating. Warner stopped him in the hall one day to ask, “Do you think the ass is too big?”

“Ty, I’m an accountant,” the executive replied.

3. Think Small

While most business owners dream of landing a big customer, Warner actively hated the idea of selling to them. From the day he started his own business, on through the end of the Beanie Babies craze, he focused his energy on selling to an enormous network of tens of thousands of small, independently owned toy and gift shops. By selling to those stores, he could avoid discounting, get paid quickly (chains generally require extended payment terms), and make sure his sales force worked directly with store owners to control how his products were displayed. He’d also avoid the risks that came with deriving too much revenue from a single customer who can stop ordering at any time.

Note: If this strategy does work, you could make some enemies. “They won’t give us any,” the main buyer for plush toys at Toys “R” Us groused to a reporter at the height of Beanie mania. “I have not been able to get them to return my phone calls. We’re extremely concerned. We’ve been shut out by Ty.”

4. Maintain Control

Warner had tons of opportunities to sell or grow his business. He could have taken a huge payday to unload it to a private equity firm or one of the publicly traded toy behemoths—and retired to spend the rest of his life sipping Mai Tais. But Ty Inc. never put itself up for sale; nor did it ever acquire another company. In an era of exit strategies and strategic planning, Warner stuck with what he did best: designing and selling stuffed animals. When the investment bankers came peddling deals that would have allowed him to leave the company with a billion in cash, Warner declined all dinner invitations.

“Most guys would at least have the decency to jerk you around,” remembers one banker. “He wouldn’t even talk to you.”

5. Reward the People Who Got You There

At the end of 1998, a year in which Warner recorded a pre-tax profit of more than $700 million—which at the time, was the single most profitable year of any company in the history of toys—he decided to do something special, to say the least: He gave every single one of his employees a cash bonus equal to their annual salary.

6. Never Change

Warner is 70 years old now, and while his remains the No. 1 plush brand in the world, his sales are a tiny fraction of what they once were. Still, as the company’s CEO and sole owner, he remains personally involved in the design of every animal that goes out the door with his world-famous Ty-heart attached.

A few years ago, Warner was sitting in his office alone, inspecting a factory sample for a new bear he was planning. He wanted it to be a pearl color, but it didn’t look quite right to him. He picked up the phone and summoned an employee who he knew wore pearl earrings. She walked in and was confused when he instructed her to take off her earrings and hand them to him.

He held them up to the bear, and then looked at both under a light. “It is not pearl!” he proclaimed. She also looked, and sure enough, he was right. She wouldn’t have noticed it at first, but now she could see: the shade of the bear’s fur wasn’t quite the same as that of the pearl earrings. To this day, why this was important remains a mystery to her; however, it was important. The prototype went back to China with instructions that the color needed to be more pearl-like.