by Isaac Elliott-Fisher, filmmaker and owner of Village Toy Castle

Can a toy commercial inspire play? Can it teach play patterns? Can it enrich a childhood through creative inspiration? Or is it just crass commercialism aimed at parents’ wallets?

For nearly 15 years, these questions have remained top of mind through my work as a documentary filmmaker exploring the history of iconic toy brands and franchises. During the COVID-19 pandemic, I began collecting interviews with industry professionals, experts, psychologists, and historians to explore the psychology, evolution, and history of toys, play, and the delicate art of marketing to children. I sought to understand how and why the changes in media and new product development and consumption impact the overall quality of childhood.

A few years ago, I set out to explore this subject as I watched my kids grow from toddlers into preschoolers and elementary school-aged little people exploring their world through play. At retail, we eventually landed in a vast wasteland of empty shelves, toys for adult collectors — or “kidults” — and easy access to addictive screens.

THE MODERN CHILDHOOD

Following World War II, cheaper materials like plastic and the introduction of TV marketing reshaped the toy industry. TV turned kids into advocates who could drive purchases with wants that parents responded to. Those desires ruffled some feathers and led to restrictions on marketing toys to kids.

In the 1980s, U.S. President Ronald Reagan deregulated the FCC opening the floodgates for toy companies to finance what were often considered 30-minute animated commercials in the form of cartoons. Brands like Masters of the Universe, Transformers, Strawberry Shortcake, and G.I. Joe led a revolution spawning a tidal wave of action figures, vehicles, and playsets for the remainder of the decade, all backed by shows, movies, and publishing programs that, with the embrace of licensing, turned brands into franchises.

CONTROL KILLED CREATIVITY; POLICY STIFLED PLAY

One could argue that this free market capitalistic frenzy created a rich environment for creativity and storytelling through competition. However, critics posited that mass consumerism was dangerous to kids and resulted in them mimicking what they saw on TV, ignoring that kids used corporate storytelling as a jumping-off point to create endless magical worlds off-screen, each powered by imaginative play.

Through my interviews, I discovered the arms-length nature of a toy company hiring an animation studio, that in turn hired freelance writers and artists who were driven not by creating toy commercials, but by crafting art that made for a rich environment of timeless storytelling. Eventually, the lobbyists won with new regulations taking effect into the 1990s.

Where creativity and collaboration once existed, toymakers created silos in which they own their artists and writers and can control their output internally.

“All the streamers and studios are really playing it safe with children’s animated content and copying each other right now,” says animation director and producer Ciro Nieli, showrunner on the 2012 Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles reboot. “And the last thing any of them are thinking about is producing shows about fighting men.”

A FRACTURED MARKET

While many like to point the finger at electronics and technology as the primary culprit in the KGOY (kids getting older younger) phenomenon, this has been occurring since the first tsunami of video game consoles and computers arrived in the ‘80s. Kids’ attention is increasingly at a premium, and while I believe that screens can take part of the blame, it’s time to take a hard look at the product offerings on the table and their marketing (or lack thereof).

As the owner of a small, destination toy store in rural Ontario, Canada, I do my best to stock a wide array of products aimed at kids in the 5-10 bracket. Each year, it becomes increasingly difficult to find new, unique, and exciting products geared toward kids in that range — especially for boys. I find it nearly impossible to find action toys that aren’t just tired, old, recycled brands that kids’ fathers played with decades ago. And in many cases, those very brands are now repositioned for adult collectors reconnecting with their childhood heroes.

Since the smashing success of Spin Master’s PAW Patrol more than a decade ago, there has been a habit of diluting popular IP by reshaping it for younger audiences. In my research, I discovered that animation studios are no longer discussing how totemic a design is — instead, they are now seeking ways to age-down every tired IP into the preschool space following a now-ubiquitous form factor. Kids don’t typically hold nostalgia for their preschool brands, but they remember what they were into in grade school.

Kids ages 5 and up no longer have a common monoculture access point to discovery. They’re not plunked in front of the TV for short bursts of entertainment before going on adventures outside. These stretches of collective experience gave kids access to a shared language of play that became “water cooler” talking points to discuss on the playground. Kids’ collective sense of culture, storytelling, experience, and creativity drove toy sales.

A STORM OF COMPLACENCY

Many of today’s kids are not allowed to go and play outside. Unlike their parents and grandparents, they won’t know a walk to the neighbor’s house with their action figure carrying case to play in the backyard or garden blowing up G.I. Joes, nor will they dig sewers for the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles or fly X-Wings through the hedgerows. Instead, modern parents have the incredibly misinformed notion that the real world is dangerous and we should keep kids inside, tethered to small, Internet-connected screens to keep them busy and protect them from danger. In reality, we’ve given them what amounts to highly addictive dopamine machines with little regard for the effects on childhood brain development.

Play researcher Dr. Kathy Hirsh-Pasek is a vocal advocate for the importance of screen-free, imaginative play as essential for kids. “If you really want to grow the CEOs of the future and not the worker bees, then allow children to play and discover and develop the actual skills they need for the modern world,” she says.

Meanwhile, parents seeking action toys for kids in the 5-10 range are surprised to discover that the industry has aged down to preschool or aged up for adults with little middle ground.

“When it comes to the phenomenon of children growing up faster, it seemed that for some time toy companies just accepted that,” says former Mattel CEO Tom Kalinske, who later led SEGA in its battle against Nintendo. He notes that the industry seems to be getting better at addressing the market shift.

CRAFTING NEW NARRATIVES

As parents, we are hijacked by the media we consume. We have to work twice as hard to manage our fears and emotions while curating content for our kids in a world where they don’t need to discover anything of their own. And this is where I’m personally torn.

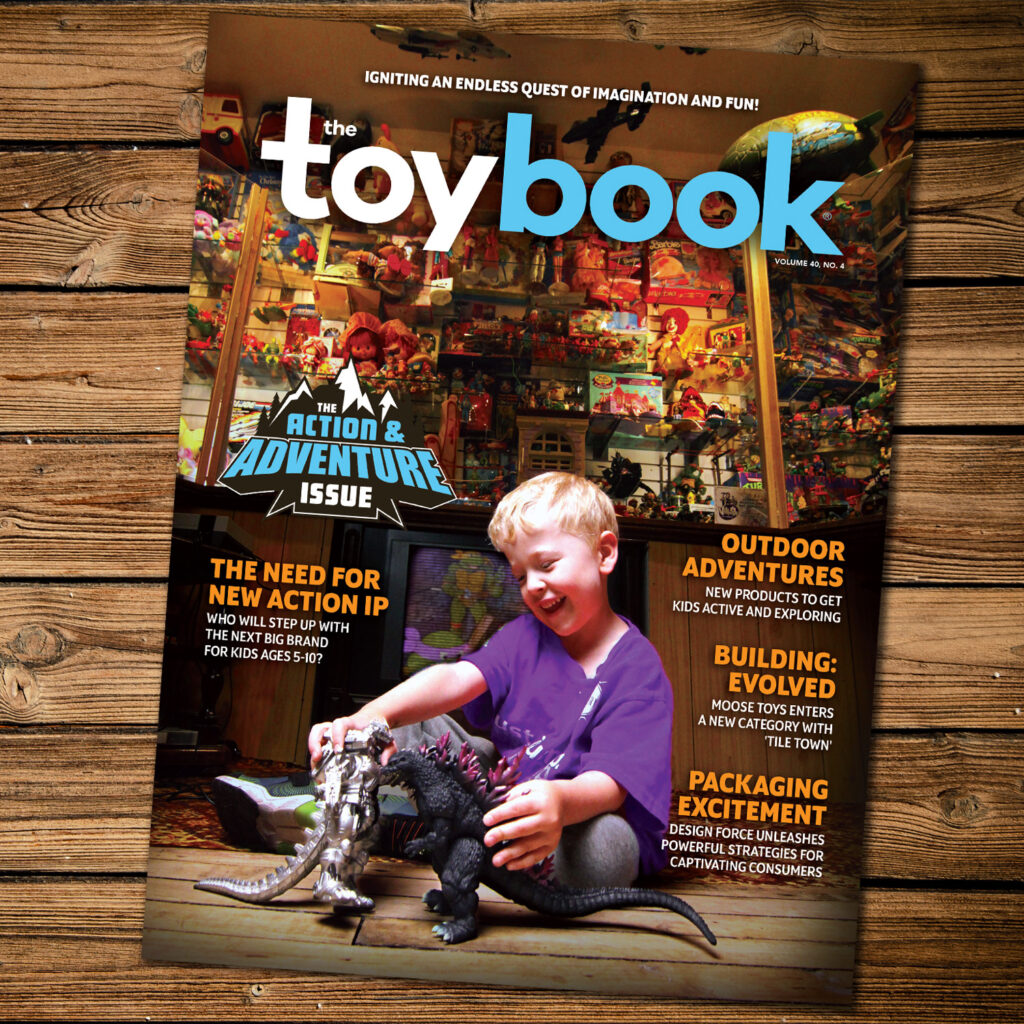

My middle son discovered the world of Godzilla through the YouTube algorithm, but the play pattern he adopted wasn’t play, it was display. He set up his many Godzilla action figures in static displays, learned from watching adults on YouTube in the mindless “content” through which they make their living. He discovered something to want and play with, but the pattern dictated is not narratively enriching, nor are there the same safeguards and regulations as there were with TV.

Kids are still kids, they haven’t changed on a biological level. They still NEED to play with their hands, outside, in the dirt, under the couch, and on the floor. The tools with which they do this can be self-made, found, or purchased, but there is nothing wrong with providing options they can discover, work for, and enjoy.

We live in a commerce-driven world that kids are a part of. Whoever cracks the code to provide them with new, creative, and exciting options will make a mint while convincing kids to put down the screens. Who will create the next iconic brand before it’s too late?

A version of this feature was originally published in the The Toy Book’s 2024 Action & Adventure Issue. Click here to read the full issue! Want to receive The Toy Book in print? Click here for subscription options!