Many of the newest games hitting store shelves and gamers’ too-full storage closets can be boiled down to a simple, three-word question: Who done it? Or, more colloquially, whodunnit?

Games that center on mystery — of both the crime-solving and social deduction persuasion — have been a long-standing staple in the category. Clue, for example, has been bringing murder mysteries to game nights for more than seven decades. However, in recent years, crime and deduction games have become increasingly popular.

Some of this trend can be attributed to the overall prevalence of true crime and murder mysteries in popular culture, with podcasts like Serial and My Favorite Murder; Netflix docuseries like Tiger King and Unsolved Mysteries; and even more lighthearted, fictional shows like The Afterparty and Only Murders in the Building dominating cultural conversation.

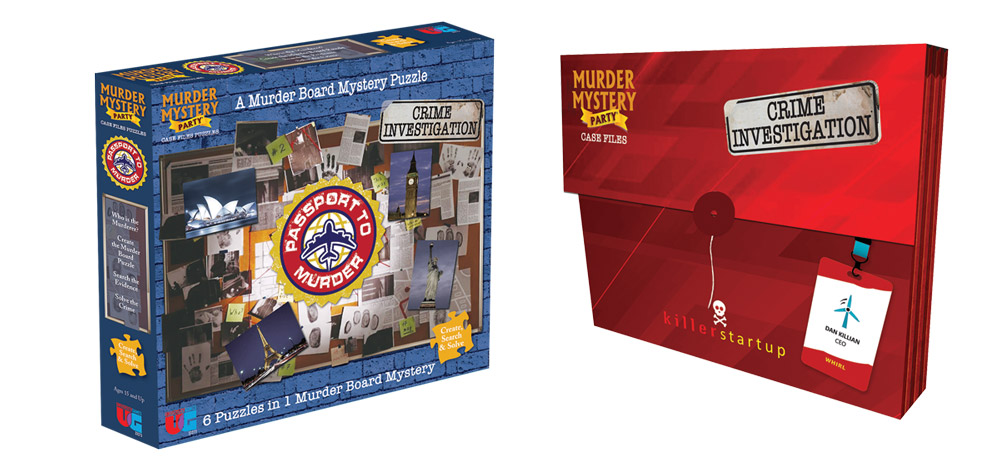

“And so it’s only the right next step that [consumers] are part of the experience,” says Craig Hendrickson, senior vice president of marketing and product development at University Games, which launched its Murder Mystery Party game line back in 1985 and has expanded its Murder Mystery offerings in recent years. “With movies and shows, you’re watching and you don’t really get to participate. With games, you get to be the detective and you get to be the one who solves the crime.”

The timing of our cultural obsession with crime and mystery has coincided with the increasing popularity of licensed board games, which means that some iconic mysteries and thrillers are getting remade for tabletop deduction.

Last year, The Op released The Thing: Infection at Outpost 31. Inspired by John Carpenter’s 1982 film The Thing, the game requires players to discover who among them has been infected by the heinous life form. “In The Thing, the movie never completely confirms who is still human at the end,” says Pat Marino, game design manager at The Op. “The story keeps that tension going, taking a group of characters who know each other well and turning them against each other; much like a social deduction game can have a group of friends suddenly unsure who at the table to trust.”

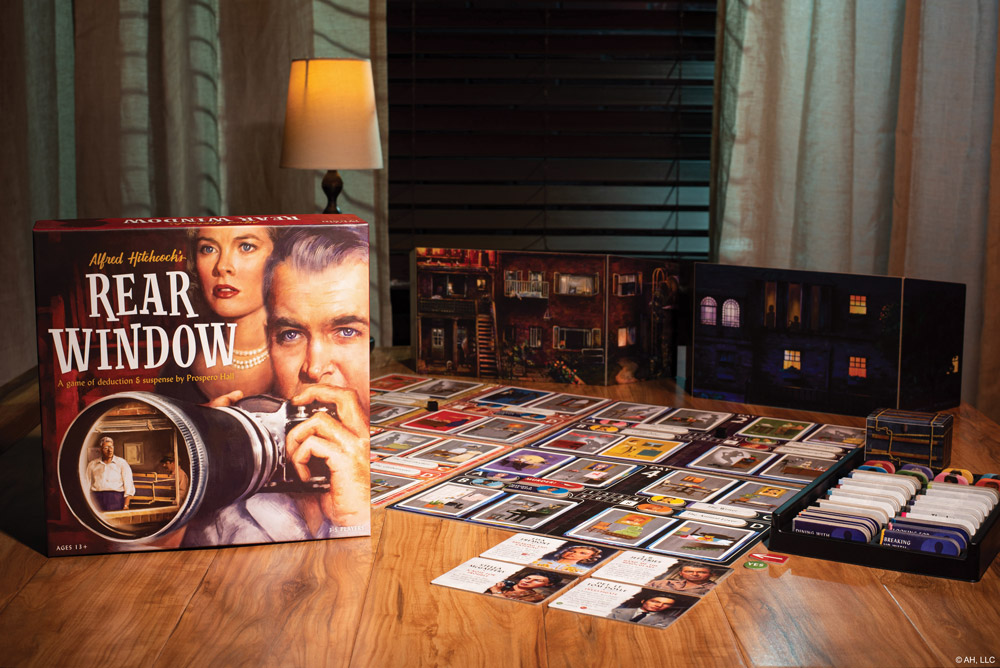

Funko Games also has a new deduction game coming out this summer, inspired by Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window. In the game, one player takes on Hitchcock’s role, trying to communicate clues to their fellow players — without words — to help them determine if a crime has been committed.

Deirdre Cross, vice president of Funko Games for sales, marketing, and business development, says these types of stories are so ingrained in society that it’s easy for players to jump in and recognize the mechanics they will be using. “Okay, so I’m trying to solve a crime. Oh, I’m in a mystery or I’m in a spy story,” she explains. “You can connect with that immediately. You understand what your motivation is in the game story.”

This leads into another reason why many working in the games industry believe that mystery and deduction attract game lovers. As Ravensburger Game Development Manager Daniel Greiner says, consumers love games that make them feel smart and productive. Ravensburger offers a variety of puzzle-based titles, including its new echoes line of audio-based mystery games.

“The goal behind these games is not to show off the cleverness of the puzzle designs, but of the players themselves,” he says. “It’s you, the player, who gets to feel clever by solving things and creating connections, by maneuvering mysterious and engaging environments.”

However, these elements have — literally — been in play for decades. So why does this particular moment lend itself to true crime and social deduction? University Games Co-Founder Bob Moog has a unique perspective, having been making murder mystery games for so long. He has noticed a major difference in the type of mysteries that modern consumers want, compared to those of the ‘80s. “Our early Murder Mystery Parties were more party, less mystery,” he explains. Now, though, he says that people are seeking out more “real” crime. Moog believes this is driven by both fear and by a desire for escapism. “I think that people have all this undiagnosed stress that they’re living with,” he says, referring to the COVID-19 pandemic, climate change concerns, economic uncertainty, and myriad other unknowns that we face.

“They’re not specifically wanting to solve murders, but they want something that will take their mind — in a really meaningful way — away from all this stress they’re carrying around,” he says. “And there’s almost nothing as intense as solving a puzzle in which you’re catching a murderer. It’s back to ‘I have some control. I’m going to make something happen.’ And that’s different than just winning a game. It’s a different sensation emotionally, and I think that’s why we’re getting so much play out of these.”

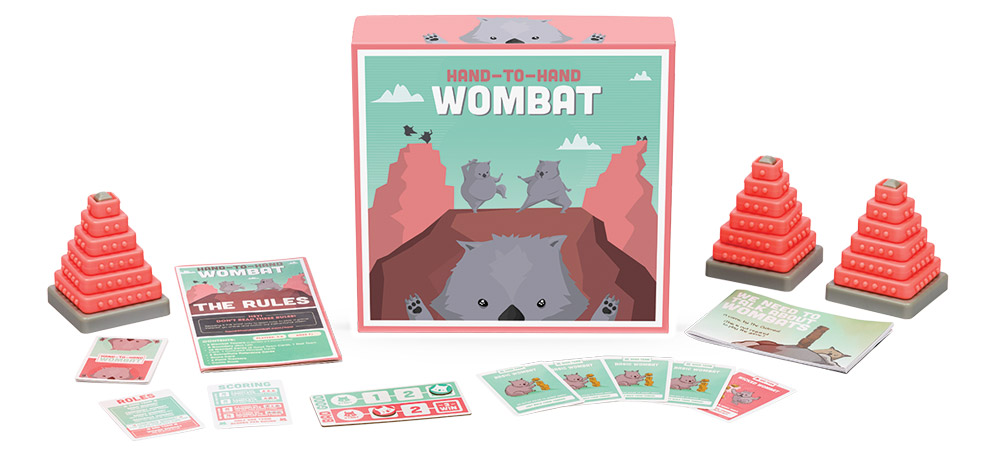

Elan Lee, CEO of Exploding Kittens, also notes escapism as a major driver in the popularity of social deduction games. Exploding Kittens has a new party game that completed a successful Kickstarter campaign in March called Hand-to-Hand Wombat. While this game doesn’t feature a true crime element, it does feature the key elements of a social deduction game. Players are randomly and secretly assigned to be “Good Wombats” or “Bad Wombats.” Then, all players close their eyes — the Good Wombats attempt to build towers while the Bad Wombats attempt to sabotage them. Then, players try to vote out the Bad Wombats.

Notably, this game also brings social deduction to a younger age demographic, with an age grade of 7 and up. Generally, as Cross says, social deduction games skew older because “kids are not great liars. … They want to be the bad guy, but they’re not so good at it.”

For Hand-to-Hand Wombat, the Exploding Kittens game designers introduced the hands-on, tower-stacking element to give kids a concrete element to reference when being deceptive.

“There’s something they can point at, so they don’t have to make eye contact or have to build a defensible stance about why it wasn’t them,” Lee explains. “Instead, [they] just point at the blocks.”

Lee, an avid lover of social deduction, says that Exploding Kittens took almost two years to develop Hand-to-Hand Wombat in order to solidify the hands-on element, the quick gameplay, and the wider age appeal.

Lee highlights that social deduction games give participants the opportunity to play a role and put on a metaphorical costume. While in their roles, he says, players get to either explore paranoia (if they are on the “good” side) or nefarious behavior (if they are “bad”). These are two behaviors that we generally avoid, but social deduction games allow players to explore them in a healthy and controlled way.

“Exploring that space is a kind of beautiful departure from where we are,” Lee says. “You’re not checking every word, you’re not scared all the time, you’re not doubting somebody’s intentions and having to do fact-checking and all of that. Instead it’s look, there’s two teams here. … I’m gonna try to figure out which of those two roles everyone at the table is. And shrinking the world down to that very black and white is refreshing. I think it’s really, really healthy right now. I think that’s why I gravitate toward [social deduction games] and why all the people I play games with are so in love with them at this moment.”

This article was originally published in the May 2022 edition of the Toy Book. Click here to read the full issue!